A cloze test is a way of testing comprehension by removing words (usually every 5th word or so) from a passage or sentence and then asking the reader/learner to supply the missing elements. For this reason, it is also sometimes referred to as a gap-fill exercise.

This learning tool has been used in the classroom since the 1950’s. The educational background of this test is from the theory of ‘closure’ in the Gestalt school of psychology, which says that the brain sees things as a whole unit and will naturally and easily fill in missing elements (Walter 1974). In other words, when information is missing, a person will use their past experiences or background knowledge in combination with critical thinking and reasoning skills to fill in the gaps.

In language learning, the closure aspect in Gestalt theory is applied by assuming that the brain views language as a whole, complete unit. The learner will naturally supply the missing elements based on their past experiences. The most common method of creating a cloze test is to apply the deletion to an entire paragraph of structurally correct and naturally occurring text. Learning focus can be applied nouns, verbs, function words, or a mixture of all types. Importantly, test designers can either allow learners to supply their own word(s) for the missing element, or give them a short list to choose from.

Example 1 below shows a traditional pen-and-paper fill-in-the-blank type cloze deletion. Figure 1 below shows an example of a computer-assisted multiple-choice type cloze deletion test.

Yesterday, Andrew went to _____ store to buy batteries.

Learners can start using these types of tools almost immediately in the language learning journey, as long as the passages are level-appropriate. In these longer exercises, words are removed at intervals from passages about anything; cooking a meals, describing a medical problem, or running an errand. In language learning literature will sometimes refer to these longer passages as MCDs (massive context cloze-deletions).

Fig. 1: Computer-assisted multiple-choice type cloze deletion test

Fig. 1: Computer-assisted multiple-choice type cloze deletion test

Who uses cloze deletion tests?

Cloze tests are primarily used in language-learning, but are also sometimes employed as a comprehension check to improve native language reading in a practice known as ‘incremental reading’. In language learning, cloze exercises may be used by beginner-level students to practice vocabulary, as well as advanced-level students to strengthen fluency and improve retention. Cloze exercises are included in language-learning software tools such as Duolingo, Anki, and Rosetta Stone, and are featured exclusively in the Clozemaster language software. Forums like Reddit and “A language learners’ forum” provide communities of students, teachers, and other professionals a platform share tips and tricks for getting the most out of cloze tests.

Why are cloze tests beneficial for learners?

Cloze exercises are beneficial for learners in many ways, but three most important are that (1) they have real-world application, (2) they provide learners with natural-like settings, and that (3) they can be flexibly and personally tailored to meet learning needs. The effectiveness of close deletion tests can and has been studied by applied linguistic researchers in a number of ways; a number of studies will be considered alongside these benefits.

Benefit of cloze tests #1: real-word application

In general, usage- or task-based techniques are the most effective language learning tools (Tomlinson). Studies have shown that young learners benefit far greater from interactive activities rather than individual work in coursebooks. Similarly, adolescent and mature learners benefit from task-based language learning that enhance and nurture their creativity, rather than simple learning by rote. Traditional vocabulary flash cards are useful for mapping individual words to their meanings, but limited in their real world application; cloze tests are the natural next step, bridging the gap between individual work and interaction. Cloze tests promote active production of vocabulary, not just recognition. They can be used to bolster vocabulary usage and free recall, reinforce grammatical knowledge and structural recognition, and strengthen overall comprehension.

In practice, it is possible that external factors such as timed tests and test-related anxiety could inhibit learners’ performance in active production. Chae and Shin (2015) found that giving participants a timed versus untimed cloze test was not a significant predictor of accuracy; however, individual reading/response time was a significant predictor of accuracy. Accurate answers had a shorter response time; in other words, participants took a shorter time when selecting correct answers than incorrect ones. This provides support to the closure idea in gestalt theory by showing that when participants are presented with a blank that they know, they fill in the gap quickly. Chae and Shin (2015) also allowed participants to pick the topic of their cloze exercises. They believe that students’ real-world experience of the topic reduced their anxiety and increased their accuracy.

Benefit of cloze tests #2: natural-like settings

A second benefit of cloze exercises are that they provide learners with natural-like settings to try out new vocabulary items. This natural input is a crucial component of what language acquisitionists sometimes refer to as “the richness of the base”. The mixture of ‘what you know you know’ with the missing items gives learners a chance to strengthen their contextual learning. In other words, practicing and internalizing how individual words work together at the sentence- and paragraph-level improves overall knowledge of the language as a whole. In speaking, mastery of vocabulary is demonstrated when a learner can use a word in original utterances in various contexts. The same concept can be applied to cloze deletion; if you can get the ‘blank’ right, you probably also know every word in the sentence. Another benefit of this method is that each instance provides learners with a reproducible frame for future application.

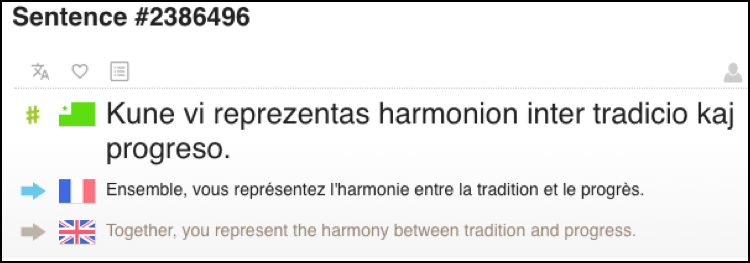

In their paper on how to improve cloze tests, Brown, Yashiro, and Ogane (1999) propose that using passages with applicable content at the correct level was more important to promoting individual success than applying the same tests universally to every participant. Ideally, cloze exercises should draw their data from a large body of natural text that is produced and vetted by native speakers. For example, the sentences used by the Clozemaster language learning tool come from the Tatoeba corpus, an ever-growing dataset of passages in many language combinations. The sentences are supplied primarily by native speakers and range in complexity from very simple to very complicated. Fig. 2 below shows an appropriate beginner-level sentence from the Tatoeba corpus. Fig. 3 shows a higher-level sentence. By relying on mostly native-speaker data, Clozemaster provides users with natural language use in a variety of natural settings. Some examples will even incorporate ‘idiom-like’ uses, such as the non-English equivalents of the common phrasal opener ‘Why on Earth […]?’ Similar types of idiomatic expressions must be ‘purchased’ through a points-award system in Duolingo. In classroom interaction, a native-speaking teacher could provide this type of content, but this depends on the flexibility of the instructor.

Fig. 2: A beginner-level sentence from the Tatoeba corpus

Fig. 2: A beginner-level sentence from the Tatoeba corpus

Fig. 3: A higher-level sentence from the Tatoeba corpus

Fig. 3: A higher-level sentence from the Tatoeba corpus

So important is the context of a cloze exercise that there is debate as to whether cloze tests are relying more on lexical knowledge or discourse competence. There is a general consensus among researchers that not all deletions are measuring the same abilities. For example, deletion of discourse markers (eg. words that indicate changes in speaker, or give sequential information like “and then”, “until”, “well”, “so”, etc.) is testing and relying on a different set of skills than testing simple lexical recall (eg. words that represent concrete items or ideas such as “dog”, “supermarket”, “angry”, etc.). Brown (2002:84) tests his hypothesis that “cloze items tap a complex combination of morpheme- to discourse-level rules” for students with different proficiencies with 336 Japanese learners of English. He demonstrates statistically that higher-proficiency learners perform differently than intermediate-proficiency learners and that these difference manifest in item type. A cloze test tailored for students at different proficiency levels draws on substantially different item types to achieve similar statistical distributions of results. These results confirm his hypothesis that depending on their proficiency, learners dodemonstrate different reliance on their lexical knowledge and their discourse competence.

Regardless of the results of the academic debate between lexical knowledge and discourse competence, both of these are valuable abilities in a language learner’s skill set. Cloze tests are included as critical components of many standardized proficiency tests or language program placement tests. Strengthening learners’ familiarity with and ability to flexibly engage with these types of tests will benefit them in multiple contexts. McCray and Brunfaut (2017) used an eye-tracking study of 28 participants to test the hypothesis that the employment of higher-level reading processes depends on test-taker performance level. They found that the number of times a participant glanced to the word bank was a significant predictor of accuracy; lower-scoring test-takers made more visits to the word bank than did higher-scoring test-takers. High performers were able to retain, recall, or naturally supply the correct words quicker than the low performers. These results suggest that both lexical knowledge and discourse competence are two of the cognitive processes governing performance of the cloze exercises.

Benefit of cloze tests #3: flexible

A third benefit of the cloze deletion exercise method is its ability to change depending on the needs of the learner. Language learning is a series of elaborate cognitive behaviors working together, rather than a uniform process. Age, environmental language exposure, language-learning experience, classroom-instrument type, and personal attitude are all important variables for each individual. Shortcomings in one variable may be compensated for by another variable. For example, older learners who have a high amount of motivation may perform similarly to younger learners with low motivation (Masgoret and Gardner). Ajideh, et al. (2017) found that individual learning strategies had an effect on cloze test performance for a group of 158 language learners in Iran. Students who learned better through indirect mental processing techniques such as planning, evaluating, seeking opportunities, controlling anxiety, increasing cooperation and empathy, and focusing performed better on the cloze tests than students who relied on the direct mental processing techniques of memorizing, analysis, compensation, and transformation or synthesis of learning materials. Because cloze tests contain a large cognitive and reasoning component, learners who use indirect learning methods may perform better on these tasks.

In the early days of computer-assisted learning, Brown, Yamashiro, and Ogane (1999) proposed three improvements that might be made to cloze tests. They called them the hit-or-miss method (in which numerous cloze tests are administered until the ‘best’ one is determined), the modified method (in which the variables are modified after administration and analysis), and the tailored-cloze method (in which the content is modified after administration and analysis). Since the advent of computer-assisted learning, all three of these techniques may be employed, and even tailored to individual learners. Anki, Duolingo, and Clozemaster are three such programs that employs these strategies, using individual performance as a point of analysis and providing tailored ‘feedback’ to learners. This flexibility of focus realizes Brown (et al.)’s vision of providing users with a dynamic learning environment that constantly adapts to their needs.

Another way that the personalization and individualization of cloze tests benefit learners is that they can be applied to a variety of grammatical or thematic environments. Grammatical elements such as adjectives, nouns, verbs, or function words like articles and prepositions may be targeted as areas of focus. Clozemaster’s Grammar Challenge feature, cloze tests grouped by grammatical elements available for a number of languages, is particularly well suited to this task. Thematic clusters like emotions, items in a doctor’s office, shopping and buying, or other subject areas can also be targeted. In addition to vocabulary, cloze exercises can also be tailored to focus on higher-level language learning such as subject-verb agreement, gender/number agreement, case, or tense consistency.

Gaillard and Tremblay (2016) compared an Elicited Imitation Task (EIT – a task in which a language learner’s oral proficiency is evaluated by repeating another speakers’ sentence) to the cloze test scores and language background demographics of French learners (including at least 6 self-identified native or heritage speakers of French). Their results found that the strongest relationship to EIT performance was cloze test performance and that it was significantly more important factor than months of residence in France, years of instruction, and age of first exposure to the French language. In other words, learners who demonstrated oral proficiency also performed well on cloze tests; their understanding of the language as a whole.

Conclusion

To summarize, language learning is invariably going to be hard work but there are a number of intervening factors that can inhibit or enhance an individual’s success. Various techniques can make language learning easier, and one of the more effective exercises are close deletion tests. Cloze deletion exercises have been used for decades by language learners of all levels, and have been shown to benefit learning in a number of ways. They emphasize usage-based learning, can be tailored to individual needs, and are flexible in their application. The advent of technology-assisted language learning has expanded the potential application of the cloze test. Language learning tools like Anki and Duolingo incorporate elements of the cloze exercises into their packages, but Clozemaster focuses exclusively on the cloze deletion principle. It uses natural text from a corpus of diverse passages supplied and vetted by native speakers. Clozemaster allows users to target specific benchmarks, such as the 100 most common words in the target language, and tailors its questions to meet those benchmarks. These features mirror the ideal cloze tests envisioned over twenty years ago by applied linguists and represent one of the better and most research-based tools in the field today.

References:

Ajideh, Parviz, Massoud Yaghoubi-Notash, and Abdolreza Khalili. “An Investigation of the Learning Strategies as Bias Factors in Second Language Cloze Tests.” Advances in Language and Literary Studies8.2 (2017): 91-100. http://journals.aiac.org.au/index.php/alls/article/view/3372 [Accessed 03 Aug 2017].

Brown, James Dean. “Do cloze tests work? Or is it just an illusion?.” University of Hawai’i Second Language Studies Paper 21 (1) (2002). http://www.hawaii.edu/sls/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/BrownCloze.pdf [Accessed 11 Aug 2017]

Brown, James Dean, Amy D. Yamashiro, and Ethel Ogane. “Tailoring Cloze: Three Ways to Improve Cloze Tests.” University of Hawai’i Working Papers in English as a Second Language 17 (2) (1999). http://hdl.handle.net/10125/40800 [Accessed 08 Aug 2017].

Gaillard, Stéphanie, and Annie Tremblay. “Linguistic Proficiency Assessment in Second Language Acquisition Research: The Elicited Imitation Task.” Language Learning 66.2 (2016): 419-447. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/lang.12157/full [Accessed 03 Aug 2017].

Masgoret, A–M., and Robert C. Gardner. “Attitudes, motivation, and second language learning: a meta–analysis of studies conducted by Gardner and associates.” Language learning 53.1 (2003): 123-163. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9922.00212/full [Accessed 08 Aug 2017].

McCray, Gareth; Brunfaut, Tineke (November 2016). “Investigating the Construct Measured by Banked Gap-fill Items: Evidence from Eye-tracking”. Language Testing. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0265532216677105 [Accessed 03 Aug 2017].

Walter, Richard. 1974. “Historical Overview of the Cloze Procedure.” Kean College of New Jersey. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED094337 [Accessed 03 Aug 2017].

Webb, Stuart and Tatsuya Nakata. “Vocabulary Learning Exercises,” in Tomlinson, Brian, ed. SLA research and materials development for language learning. Routledge, 2016: 123 – 138.

Pingback: How Cloze Tests Help You Learn A Language 5x Faster - Clozemaster Blog